Spoliation sanctions. Two words no-in-house counsel or law firm litigator ever wants to hear, but a routeinely-deployed threat when a disagreement about the availability of ESI arises.

Last fall, Roost Project, LLC v. Andersen Construction Company featured a dispute about.mpp files (.mpp files are associated with Microsoft Project, a software commonly used by project managers, team members, and stakeholders).

Background of the Case

The Roost Project, LLC (Roost) and Anderson Construction Company (ACCO) entered a construction contract in December 2015. There were many delays in the project, which resulted in completion occurring eight months after the initial contract competition date, as well as several claims and counterclaims between the parties, including breach of contract, fraud, and breach of implied warranty of workmanship.

As part of these claims, Roost argued that ACCO failed to preserve electronically stored information (ESI), the loss of which was prejudicial to Roost. Roost requested that the court impose sanctions under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e)(1) for ACCO’s alleged failure to preserve said ESI. Roost Project, LLC v. Andersen Constr. Co., 2020 WL 6273977, at *1-2 (D. Idaho Oct. 26, 2020).

The ESI At Issue

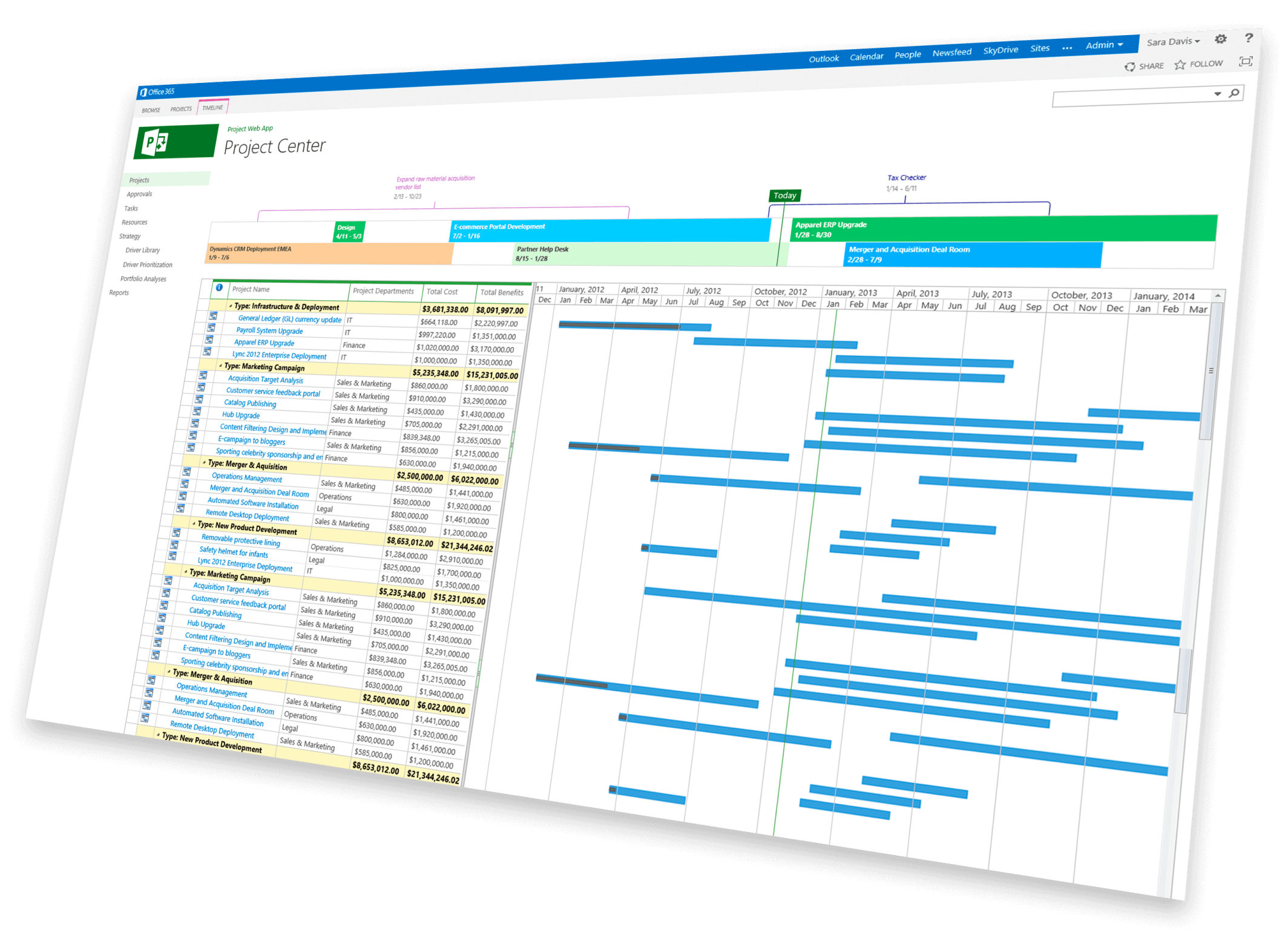

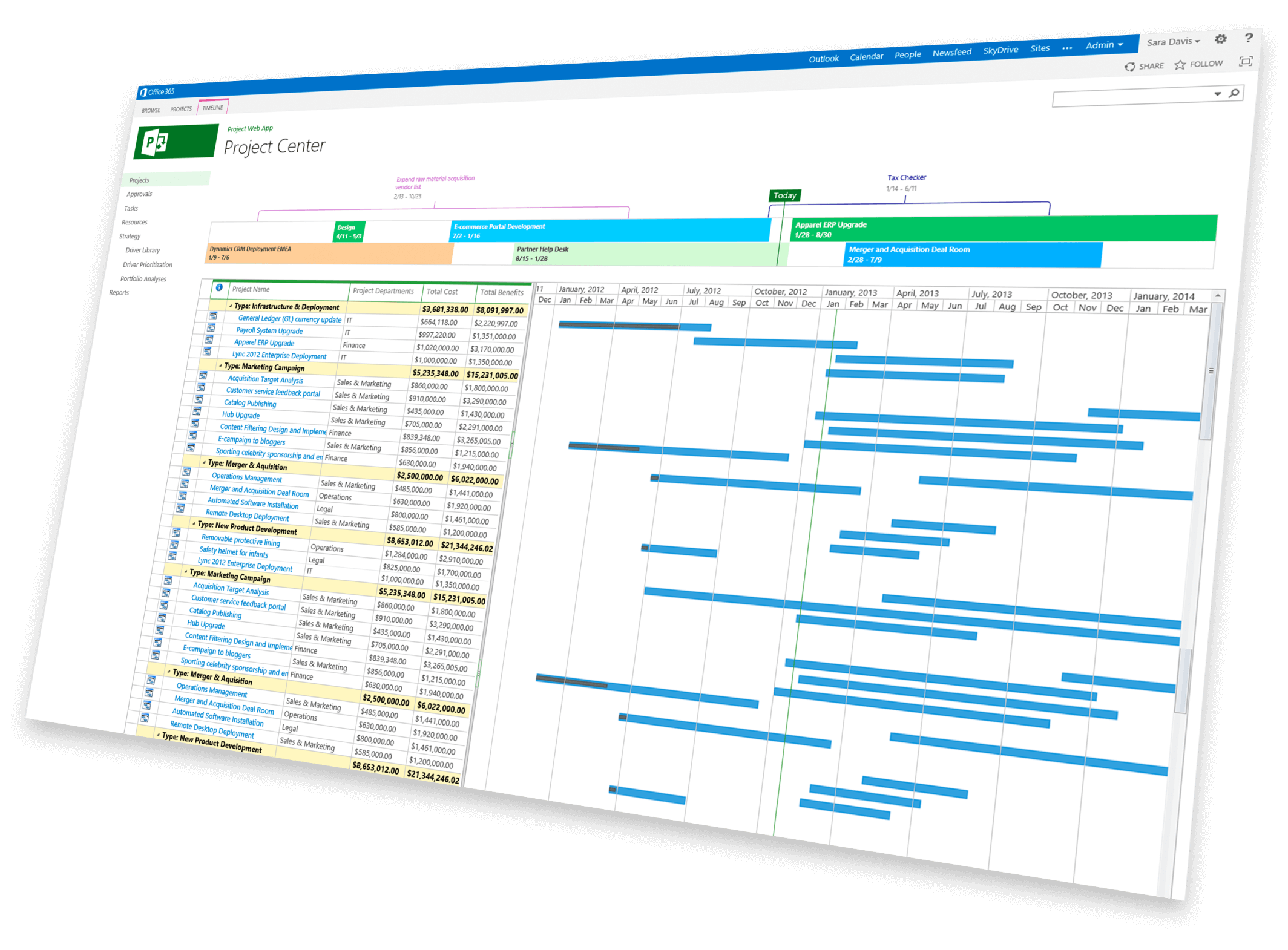

During construction, ACCO provided Roost with electronic schedule updates on the project. Prior to June 7, 2016, these schedule updates were sent to Roost in a Microsoft Project format (“.mpp”). From June 7, 2016 to January 5, 2018, Roost received schedule updates from ACCO only in portable document format. Id. at *3.

Roost argued that the native .mpp files contained important schedule logic information and data that was not included in the .pdf versions, specifically information describing when revisions were made or when delays were first identified. Roost contended that the scheduling data was lost because ACCO wrote over the .mpp files without saving the native .mpp files of the prior schedule when converting the files to .pdf format. Id. at *3.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 37(e) and Spoliation of ESI Evidence

Spoliation of ESI evidence is governed by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e). The court’s analysis breaks Rule 37 down as follows:

Four Factor Test

Under Rule 37(e), the Court assesses four factors:

- Whether the information qualifies as ESI

- Whether the ESI is “lost” and “cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery”

- Whether the ESI “should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation”

- Whether the responding party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve the ESI.

Id. at *2. (citing Colonies Partners, L.P. v. County of San Bernardino, No. 5:18-cv-00420-JGB (SHK), 2020 WL 1496444, at * 3 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 27, 2020); Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(e).)

Whether the information qualifies as ESI

In the context of Roost, the .mpp files and data contained in the .mpp files constitute ESI for the purposes of Rule 37. Id. at *3.

Whether the ESI is “lost” and “cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery”

Under Rule 37(e), information or data that should have been preserved is “lost” if it “cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery.” Id. at *3 (citing Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(e)).

The parties disputed whether data was irretrievably lost, specifically the data that would readily identify which .mpp files correlated to a specific .pdf. ACCO conceded that it did not preserve the data that could be used to readily correlate the two file types; however, ACCO represented that no .mpp files were deleted, and it produced every .mpp in its possession, custody, and control, along with the .pdf files. ACCO also represented that the produced files were dated and contained metadata. Id at *3.

Roost maintained that the .mpp files produced in discovery could not be established as the actual schedule updates correlating to the .pdf files. The court found that Roost failed to show that the schedule logic it contended was lost was not contained in the .mpp that were produced in discovery given ACCO’s representation that the dated files and metadata in the .mpp files that were produced would enable Roost or its expert to see when changes were made and when each file was saved. Id. at *3-4. In other words, Roost did not establish that the information it was seeking could not be replaced through additional discovery or alternate means.

Whether the ESI “should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation”

The duty to preserve arises when “litigation is reasonably foreseeable.” Id. at *4 (citing Fed. R. Civ. P. 37, Advisory Committee Notes to the 2015 Amendment.) The court found that the duty to preserve arose in May 2017 when the parties hired attorneys and exchanged demand letters, at which point “the likelihood of legal action was evident.” Id. at *4.

Whether the responding party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve the ESI

A party engages in spoliation “only if [it] had ‘some notice that the documents were potentially relevant’ to the litigation before they were destroyed.” Id. at *4 (citing Kitsap Physicians Serv., 314 F. 3d at 1001 (quoting Akiona, 938 F.2d at 161)). A “party does not engage in spoliation when, without notice of the evidence’s potential relevance, it destroys the evidence according to its policy or in the normal course of its business.” Id. at *4 (citing Ousdale v. Target Corp., No. 2:17-cv-2749-APG-NJK, 2019 WL 3502887, at *3 (D. Nev. Aug. 1, 2019) (citing United States v. $40,955.00 in U.S. Currency, 554 F.3d 752, 758 (9th Cir. 2009))).

In spring 2016, Roost requested .pdf versions of the schedule updates, and in June 2016, ACCO began sending only .pdf updates and continued to do so for almost a year without Roost expressing any concern or objection. Roost did not request to correlate .mpp files at that time. The court found that while it was foreseeable that schedule updates would be relevant to the parties’ dispute, ACCO did not have notice that it needed to change its schedule practices to preserve after May 2017, when the duty to preserve arose, and it was reasonable to continue its practice of writing over the .mpp files and providing the .pdf format to Roost. Id. at *5.

Prejudice and Sanctions

If these factors are satisfied, and the Court finds there is “prejudice to another party from [the] loss of the [ESI],” the Court may “order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice.” Id. at *2 (citing Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(e)(1)). If the party that was required to preserve the ESI “acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information's use in the litigation,” Rule 37(e)(2) authorizes the following sanctions: 1) a presumption that the lost information was unfavorable to the non-moving party; 2) instructing the jury that it may or must presume the information was unfavorable to the non-moving party; or 3) dismiss the action or enter a default judgment. Id. at *2.

“‘The applicable standard of proof for spoliation in the Ninth Circuit appears to be by a preponderance of the evidence.’” Id at *2 (citing Compass Bank, 104 F.Supp.3d at 1052-53). The party moving for spoliation sanctions under Rule 37 bears the burden of establishing spoliation by demonstrating that the non-moving party destroyed information or data and had some notice that the information or data was potentially relevant to the litigation before it was destroyed. Id at *2 (citing Ryan v. Editions Ltd. West, Inc., 786 F.3d 754, 766 (9th Cir. 2015); see also Kitsap Physicians Serv., 314 F.3d at 1001.)

The court reserved its ruling on whether Roost suffered prejudice from spoliation, if any.

What It Means/Why It Matters

A “party does not engage in spoliation when, without notice of the evidence's potential relevance, it destroys the evidence according to its policy or in the normal course of its business.”

Id. at *2 (citing Ousdale v. Target Corp., No. 2:17-cv-2749-APG-NJK, 2019 WL 3502887, at *3 (D. Nev. Aug. 1, 2019) (citing United States v. $40,955.00 in U.S. Currency, 554 F.3d 752, 758 (9th Cir. 2009))).

As a plaintiff, if you think certain ESI is going to be important for litigation, be sure to specify such early in the litigation to put the defendant on notice of its relevance.

As a defendant, the duty to preserve ESI arises when litigation is reasonably foreseeable, and ESI, especially that which is potentially relevant, must be preserved.

If you'd like to discuss ideas addressed here, let us know. We can help.